GLOBAL STATUS OF SCHOOL SAFETY

Key Findings from the 2024 Comprehensive School Safety Policy Survey

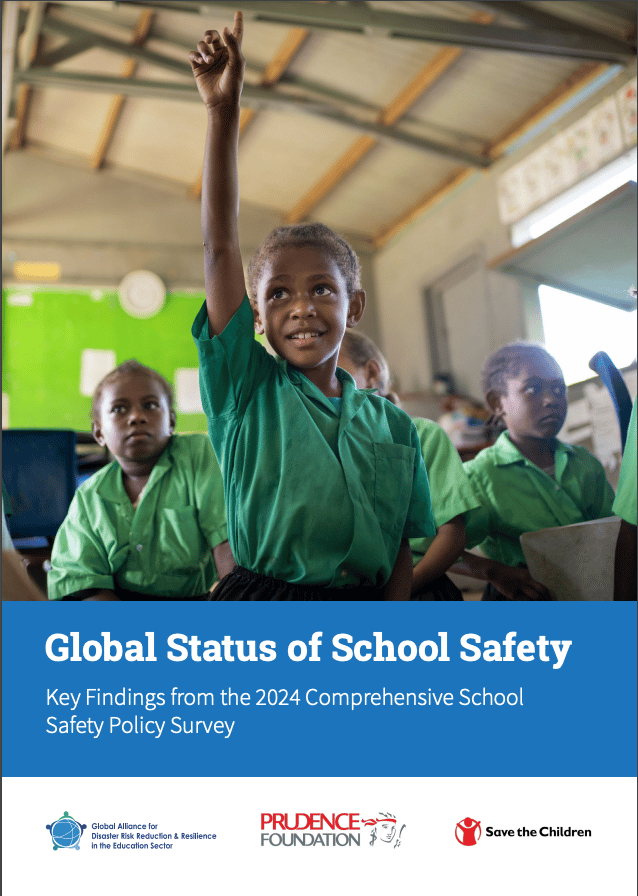

Daniela is 7 years old, and she attends school on an island in Shefa Province, Vanuatu.

Her school is part of an initiative to provide essential support during disasters to protect the safety and wellbeing of children. The initiative is a collaboration between Save the Children and the Vanuatu Ministry of Education.

Copyright: Conor Ashleigh / Save the Children.

In an informal camp in Raqqa, Syria, Abbas, 9, plays outside his tent with his siblings.

Copyright: Roni Ahmed / Save the Children.

Global Status of School Safety

Key Findings from the 2024 Comprehensive School Safety Policy Survey

Education is the foundation for a better future, empowering children and youth, strengthening communities, and driving social and economic progress. In 2015, world leaders made a promise to realise this foundation for every child through the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Yet an alarming global backdrop of the climate crisis and increasing conflicts is undermining this promise, with a lack of preparedness leaving education systems at risk. While some crises are unprecedented, some are more predictable, cyclical and anticipated, enabling the mitigation of potential effects.

But even while hazards are inevitable, the adverse impacts on children’s learning are not. With less than five years left to achieve the SDGs, the clock is ticking to protect education from the shocks we know are coming. Experience and expertise gathered from decades of work in school safety and resilience have culminated in a framework for a different future: the Comprehensive School Safety Framework.

The Comprehensive School Safety Framework

The Comprehensive School Safety Framework is an evidence-based approach to protecting children and education systems from a range of crises and disasters. The Framework includes recommendations, roles, and responsibilities for all aspects of school safety, covering three pillars:

- Pillar 1: Safer learning facilities, to strengthen the resilience of education systems.

- Pillar 2: School safety and education continuity management, to keep schools open and children learning in times of crisis.

- Pillar 3: Risk reduction and resilience education, to provide children with the skills, knowledge and behaviours to prepare for and respond to shocks and stresses.

These pillars are connected to existing education and Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) approaches through enabling systems and policies, also defined in the Framework.

Importantly, the Framework adopts an all-hazards, all-risks approach, reflecting the reality of many countries and making it relevant for a wide range of everyday risks, disasters and the compounding effect of multiple crises.

This policy brief paints a picture of the global status of implementation of the Comprehensive School Safety Framework, summarising the key findings of the 2024 Comprehensive School Safety Policy Survey.

Julian making his drawing of the risk map at his school during a Community Club session, Mexico.

Copyright: Miguel Vera / Save the Children Mexico.

About the findings

In 2024, the Global Alliance for Disaster Risk Reduction and Resilience in the Education Sector (GADRRRES) conducted a global policy survey to assess the status of comprehensive school safety around the world. Built on the Comprehensive School Safety Framework, the policy survey was a collaborative, multi-stakeholder process that engaged ministries of education, national disaster management agencies, UN agencies, national, community, and international non-governmental organisations, and more.

In total, 46 countries, two island territories, and 21 sub-national units participated, representing over 330 million school-aged children.

Participation was voluntary, leading to findings that likely overstate the robustness of school safety policy across the globe and are not wholly representative of all regions. The survey itself was also limited, given it is not possible to fully capture the range of comprehensive school safety issues nor the diversity of policies and implementation practices globally in one survey.

Because of these and other limitations, the findings and this policy brief should be understood as a starting point. GADRRRES strongly encourages more research to deepen the understanding of the global status of comprehensive school safety.

Discover the 2017 Comprehensive School Safety Policy Survey Findings

A note on terminology

The term ‘governments’ is used throughout to reflect the countries, territories, and sub-national units that responded to the survey.

KEY FINDING 1:

National governments recognise comprehensive school safety but some lack critical coordination bodies for implementation.

Suvd-Erdene, 13, is from a family of herders in Mongolia. The climate crisis is impacting their livelihood, and her mother says herding is not a future she wants for her children. Suvd-Erdene wants to train to be a teacher.

Copyright: Yondonjamts Nyamdamvaa / Save the Children.

KEY FINDING 1:

National governments recognise comprehensive school safety but some lack critical coordination bodies for implementation.

What we found

National governments that participated in the survey show a high level of familiarity with the Comprehensive School Safety Framework, with half (51%) endorsing the Framework. The recognition of the importance of school safety is further supported by the fact that over 70% of countries reported having a designated senior management focal point for school safety, providing a strong foundation for scaling up implementation and coordination.

71%

Governments with a designated senior management focal point for school safety

However, significant gaps remain. Less than one-third of national governments (31%) were using the Framework to guide policies and planning. Government-led, national school safety coordinating bodies, a primary driver of action in the Framework, were similarly lacking. Less than two-thirds (61%) of governments said this was in place.

Familiarity, Endorsement and Use of Guidance, Comprehensive School Safety Framework

Why this matters

Endorsement of the Comprehensive School Safety Framework is a critical first step for securing high-level political will behind this agenda. Endorsement means governments commit to work towards implementing and institutionalising the three pillars and foundation of the Framework.

But while endorsement is a crucial step, it does not necessarily translate into effective implementation. The gap between endorsement and implementation highlights the need for greater support and targeted efforts to ensure that commitments are translated into concrete actions. The high volume of designated focal points demonstrates that it is possible to fill this gap.

What should change

All governments should:

- Endorse, implement, monitor and report, and champion the Comprehensive School Safety Framework.

- Establish, lead, and maintain an ongoing national, multistakeholder, school safety coordination body to maximise collective impact and cross-sectoral alignment for school safety.

- Designate a high-level senior official as a comprehensive school safety focal point within the education authority.

Sandi, 9, is a refugee who was forced to flee conflict in Iraq and now lives in a displacement camp in Syria. She and her siblings are attending school for the first time in their lives.

Copyright: Roni Ahmed / Save the Children

KEY FINDING 2:

Many governments are making plans to keep children learning in emergencies, but these must be updated and implemented to be effective.

KEY FINDING 2:

Many governments are making plans to keep children learning in emergencies, but these must be updated and implemented to be effective.

What we found

Governments are planning for educational continuity on an impressive scale. Nine in 10 (94%) report having policies or legal frameworks in place for educational continuity management, though only half (54%) were developing plans for educational continuity that cover many or most risks. At the school level, guidance is provided by 98% of governments to support educational continuity planning.

94%

Governments with policies or legal frameworks in place for educational continuity management

However, the reach and robustness of this preparedness is limited. While policies and legal frameworks are abundant, one in three governments (34%) stated these were weak or unenforced. With regards to plans, a lack of monitoring and updating could undermine their effectiveness, with less than one-third of governments (30%) reporting that schools review them on an annual basis. And while guidance is also widely available, nearly half of responding governments (46%) stated this guidance was limited, poorly distributed, or poorly understood.

Plans and policies may also be limited in their reach due to a lack of consideration for the specific needs of some children. Immigrant and refugee students were the least likely to have their needs considered, with less than one-third (30%) of governments considering their needs in educational continuity planning in a robust way.

Educational Continuity Planning Considerations for Specific Needs

Why this matters

Keeping children learning in emergencies is essential for ensuring they can continue to develop the knowledge and skills they need to thrive. Disruption to learning can lead to exponential impacts on education, setting back years of progress and in the worst cases meaning children drop out of school altogether.

In emergencies, schools are also more than just centres for learning; education can help children stay physically and psychologically safe. Schools can provide many of the basic services that children need to survive, such as nutritious food and vaccinations. Schools also keep children out of harm's way, as children who are out of school are more likely to be recruited into armed forces. Finally, the normality of school can give children the stability and support they urgently need in crises, providing hope for a better future.

What should change

All governments should:

- Develop, disseminate, monitor, and regularly update national-level policies and plans for educational continuity management.

- Equip schools with comprehensive guidance to design, implement, and monitor localised plans for education continuity, including in emergencies.

- Ensure all educational continuity planning provides support for contextually-relevant curriculum adaptations and alternative methods of delivery (such as radio learning).

- Ensure the needs of all children are recognised and considered in all educational continuity planning, policies, and guidance.

KEY FINDING 3:

Investment in infrastructure is needed to better protect children and teachers from natural hazards.

An earthquake of magnitude 5.6 was centred in the Cianjur region of West Java province in Indonesia, triggering landslides and causing buildings to collapse, including schools where classes were underway, including this school supported by Save the Children.

Copyright: Alfiyya Haq / Save the Children.

KEY FINDING 3:

Investment in infrastructure is needed to better protect children and teachers from natural hazards.

What we found

Natural hazards can have a profound impact on schools. For over 75% of governments that responded, high winds and earthquakes caused damage to infrastructure. One in three governments (34%) reported earthquakes as leading to deaths in school, making earthquakes the hazard most often linked to death in schools.

34%

Governments reported earthquakes as

leading to deaths in school

Governments are making efforts to understand these hazards, with over half (61%) reporting systematic assessment of the safety of their existing school buildings.

These assessments are the first step in understanding what must be done to ensure school buildings are safe for students and staff. Complementary to this, nearly all governments have regulations for designing and constructing schools to withstand natural hazards and over half (59%) state these regulations are robust and monitored.

Investment to support these assessments and regulations do not match the level of need, however. Just 13% of governments report having consistent and sufficient funding for routine maintenance of school buildings and sites and just under 12% report systematically funded upgrades of school buildings.

Impacts of Natural Hazards on Schools: High Winds

Impacts of Natural Hazards on Schools: Earthquakes

What is ‘natural’? Disaster vs. Hazards

Simply put, hazards may be natural, but disasters are not.[1]

Natural hazards include storms, fires, earthquakes, and other naturally occurring phenomena that will happen regardless of human activity. Disasters result from a failure of society to anticipate, learn from, plan for, and protect against these hazards.

Natural hazards themselves, however, are not only natural. Human activity is increasingly worsening the negative impacts of natural hazards. For example, fire suppression and development in flood plains can intensify future fires and floods. The climate crisis can also exacerbate natural hazards, such as long-term changes to weather patterns that lead to extreme cold or heat or worsening storms. These factors must be considered when examining ‘natural’ hazards.

1 See United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction’s #NoNaturalDisasters campaign: https://www.undrr.org/our-impact/campaigns/no-natural-disasters.

Hazards Addressed During School Design and Construction

EARTHQUAKES

BUILDING FIRE

HIGH WINDS

Why this matters

Natural hazards regularly destroy school buildings if they are not disaster-proof, causing physical and financial damage and – in the worst cases – leading to deaths of children, teachers, and school staff. With the high number of governments reporting damage from natural hazards, and the compounding impact climate change may have on these, it is essential that resilient infrastructure is scaled up to keep children safe and learning. Not doing so not only puts children’s safety at risk, but also their futures, with unfixed damage to infrastructure potentially limiting children’s access to learning in the long-term.

What should change

All governments should:

- Identify, prioritise, and upgrade or replace unsafe or older school buildings, ensuring sufficient funding for this purpose.

- Engage in annual assessments of education sector exposure to natural hazards and estimate potential impacts.

- Update, disseminate, and implement policy to limit the placement of schools in river and coastal floodplains.

- Use building code regulations and monitoring to ensure school buildings can withstand expected natural hazards, including earthquakes and high winds, without collapsing.

KEY FINDING 4:

Climate change adaptation must be accelerated across the education sector.

Fahima, 25 and her daughters, Nishi, 7 and Rina, 4 were forced to leave their home following flash floods in Moulvibazar, North-East Bangladesh.

Copyright: Rubina Hoque / Save the Children.

KEY FINDING 4:

Climate change adaptation must be accelerated across the education sector.

What we found

The climate crisis is likely to exacerbate many natural hazards, and indeed climate change arose as a clear concern through the survey with 88% of governments highlighting climate change impacts, or the exacerbation of other risks due to climate change, as affecting many, most, or all schools. Other climate-exacerbated hazards were also reported by most governments, including flooding (90%), extreme temperatures (73%), and wildfires (55%).

21%

Governments reported completing full risk assessments on climate change risk.

Reflecting this degree of impact, nearly four in five (79%) governments reported that education authorities have developed plans for climate change adaptation.

Guidance for Climate Change Adaptation & Action

Despite this, almost half of governments (48%) rated their policies or legal frameworks for climate change adaptation in the education sector as weak or unenforced. Just one in five (21%) reported doing full risk assessments on climate change risk. Similarly, one in five (20%) had robust guidance on school safety planning for climate change adaptation and action. Worryingly, no governments indicated that they were engaging in systematic upgrades of school buildings for climate change.

Education Sector Risk Assessment for Climate Change

Why this matters

The climate crisis is already leading to widespread impacts on children’s right to learn. In 2024 alone, 242 million children experienced disruption to schooling due to climate events. Impacts of climate change on education can include school closures due to storms, poorer academic outcomes due to extreme temperatures, or children leaving school due to economic repercussions, among others. But while disruption can have devastating consequences for children’s learning, education is also a powerful force for positive change. Investments in resilient schools and education systems can reduce climate risks for 275 million children. Disaster risk reduction education improves children’s and communities’ resilience in the face of crises, teaching them the lifesaving knowledge and skills they need when disaster strikes. Education also promotes peaceful societies and economic prosperity, giving children hope for a better life after crises hit.

Defining climate change mitigation and adaptation in education

The climate crisis is a children’s crisis, impacting many aspects of their lives - including education. As such, schools must be part of both climate change mitigation and adaptation efforts. Climate change mitigation involves reducing greenhouse gas emissions to limit future warming; this means efforts to prevent or reduce the severity of climate change, for example by switching to renewable energy, increasing energy efficiency, or reforestation to absorb carbon dioxide. Adaptation focusses on adjusting systems and practices to cope with the current and expected impacts of climate change; for example, building flood defenses, adopting drought-resistant crops, or redesigning infrastructure.[2]

Climate change education can strengthen mitigation, helping communities act to limit climate change and prevent the worst outcomes of the climate crisis. Equally important is adaptation, including protecting education systems and structures from existing climate-related impacts.

2 For more detailed definitions, see: IPCC_AR6_WGII_Annex-II.pdf.

What should change

All governments should:

- Ensure climate change adaptation is part of education sector plans, policies, programmes, and risk assessments, including school improvement plans.

- Embed education and school safety in national, regional, and local climate change policies, processes, programmes, and funding.

- Ensure education and school safety are integrated comprehensively in National Adaptation Plans and Nationally Determined Contributions.

- Strengthen disaster risk reduction and climate change education in the curriculum and provide adequate funding and training to ensure effective implementation.

UNESCO led school-based activities to help children halt the spread of cholera during an outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Copyright: UNESCO.

KEY FINDING 5:

Health hazards are significant in scope but lack resourcing for robust response.

KEY FINDING 5:

Health hazards are significant in scope but lack resourcing for robust response.

What we found

Health hazards are among the most recognised by governments, with most (91%) reporting national strategies and school policies for health promotion. Similarly, many governments noted that they are educating students about this hazard: almost all governments include health and well-being in the primary (87%) and secondary (82%) curricula.

This widespread policy coverage reflects the level of impact, with nearly three in four governments (72%) reporting biological and

91%

Governments reporting national strategies and school policies for health promotion

health hazards as affecting education. For over half (58%) of the participating governments, these hazards lead to school closures.

What we found

Health hazards are among the most recognised by governments, with most (91%) reporting national strategies and school policies for health promotion. Similarly, many governments noted that they are educating students about this hazard: almost all governments include health and well-being in the primary (87%) and secondary (82%) curricula.

This widespread policy coverage reflects the level of impact, with nearly three in four governments (72%) reporting biological and health hazards as affecting education. For over half (58%) of the participating governments, these hazards lead to school closures.

National Strategy for Health Promotion in Schools

Despite this level of ambition and impact, resourcing hampers implementation. Just one in four governments (28%) reported sufficient funding for health, nutrition, and well-being. While many (62%) have systematically assessed and prioritised Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) facilities for upgrades, few (14%) have completed them. This is in line with responses suggesting just 16% of governments have consistent and sufficient funding for routine maintenance of WASH facilities.

Why this matters

At its peak, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted education for 1.6 billion learners across the globe, leading to as much as 2.8 years of lost learning. More localised disease outbreaks, such as cholera, similarly lead to school closures, particularly as schools are ripe for disease spread after environmental disasters. As the climate crisis deepens, the expected increase in these disasters will only worsen the spread of diseases and make the need for protocols for safe schools, educational continuity, and catch-up more acute.

Heat waves are worsened by the climate crisis, affecting children’s cognition, behaviour, sleep, and learning. This makes protocols for keeping children cool at school, as well as ensuring school staff and students understand and use these protocols, essential.

What should change

All governments should:

- Educate and assess teachers and students about health and diseases that pose a risk to the school community, including developing education campaigns that communicate life-saving health information.

- Ensure adequate funding of health, nutrition, and well-being in education.

- Fund routine maintenance and upgrades of WASH facilities, ensuring they are gender-responsive.

- Track, trace, and halt the spread of communicable disease in schools.

Children from Nigeria made some drawings to express their hopes of life in peace, with no conflict.

Copyright: Save the Children.

KEY FINDING 6:

Bullying and violence have widespread impact on children’s rights to learn and be safe.

KEY FINDING 6:

Bullying and violence have widespread impact on children’s rights to learn and be safe.

What we found

Bullying and violence continue to plague schools across the globe. Nine in 10 governments (90%) identify bullying and violence as a hazard affecting education, with over half (57%) stating that this led to school injuries. Sadly, nearly one in four (24%) reported that bullying and violence have resulted in deaths.

Policies to address bullying and violence fail to match the intensity of the challenge. Just half of participating governments (55%) reported that many or most schools proactively attempt to prevent bullying, gender-based violence, and attacks on the way to school.

24%

Governments reporting that bullying and violence have resulted in deaths

Violent Incidents Against Children or Staff, Data Disaggregation by Gender & Disability

More broadly, governments reported gaps in understanding the challenges associated with bullying and violence. Nearly half (45%) of governments do not disaggregate data on violence against students and staff by gender or disability. And while most students are taught and assessed on social and emotional learning (SEL) – a critical response to bullying and violence – just 21% of governments assessed teachers on SEL.

Why this matters

Bullying and violence is a major hazard for children. One in three students is bullied at school every month, leading to physical and psychological harm. Other forms of violence can further affect children’s ability to attend or learn at school. The impacts of bullying and violence can be particularly acute for already disadvantaged learners, exacerbating existing barriers to education for children from minority groups, girls, and children with disabilities.

SEL is one tool for reducing and responding to bullying and violence in schools. However, schools also need robust policies, training, and interventions to keep children safe from these hazards.

What should change

All governments should:

- Implement a robust national policy for equal access to safe and inclusive education for all.

- Collect and document data on violence and bullying, disaggregated by gender and disability.

- Create strategies to make school routes safer and take measures to prevent violence on the way to school.

- Train and assess teachers in the provision of SEL and psychosocial support.

Teachers participating in a training session in Indonesia.

Copyright: Plan International.

KEY FINDING 7:

Significant gaps in mandatory teacher training challenge comprehensive school safety implementation.

KEY FINDING 7:

Significant gaps in mandatory teacher training challenge comprehensive school safety implementation.

What we found

The findings suggest that many governments recognise the value of teachers in comprehensive school safety. Nearly all governments (97%) seek some input from teachers and school staff in developing risk and response management plans. Despite this, staff are not receiving the training required to develop the skills they need to confidently advance comprehensive school safety.

Just 16% of governments report that teacher training on disaster risk reduction is mandatory, with this number only rising slightly to 18% for climate change adaptation.

97%

Governments seeking some input from teachers and school staff in developing risk and response management plans

Even fewer governments - just 11% - undertake teacher development and assessment on disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation. This is despite the significant hazards posed to education by environmental and climate-related hazards, as highlighted above.

Similarly, despite the importance of social and emotional learning for tackling and responding to bullying and violence, just 30% of governments reported mandatory teacher training in this field and just 21% develop and assess teachers’ capacity for social and emotional learning. While their skills are valued and the subjects recognised as important, support for teachers to deliver is limited.

CLIMATE CHANGE ACTION

SOCIAL AND EMOTIONAL LEARNING

Is Teacher Training Mandatory Across Different Aspects of Comprehensive School Safety?

DISASTER RISK REDUCTION

Why this matters

Teachers are at the heart of quality education. Children will only receive as good an education as their teacher has been supported to deliver. In order to fulfil this role, teachers need effective training, capacity development, and assessment before and during their time in the classroom. This includes ensuring teachers are able to deliver education post-disaster through adapted methodologies.

In times of crisis, teachers are not just educators – they provide life-saving information, emotional support, and often take on community leadership roles. To ensure teachers can also operate in these roles, they must be trained in the essential skills they need to keep themselves and their students safe. Moreover, teachers are people, often as affected by the crisis as the students they teach. Teachers’ well-being must be recognised and supported by governments in order to support their own needs and ensure they can respond effectively to the needs of their students.

What should change

All governments should:

- Ensure teachers and/or sector representatives are included in developing risk assessments and response plans at the school, local, and national levels.

- Embed disaster risk reduction and climate change content in mandatory pre- and in-service teacher training.

- Ensure teacher training supports inclusive and gender-responsive strategies, including in relation to school safety.

- Provide training and support to adapt teaching methodologies post-disaster, including for remote learning, multigrade methodologies and catch-up initiatives.

- Invest in teacher well-being, providing good working conditions, mental health support, stress management, peer collaboration, and specialised care when required.

KEY FINDING 8:

Comprehensive school safety begins and ends with children.

Amaya, 6, lives in Guerrero State, Mexico. Her family lost everything after Hurricane Otis in 2023 and Hurricane John in 2024. Amaya participated in the Community Learning Clubs and the Safe School Clubs, which helped her recover emotionally after her experiences.

Copyright: Miguel Vera / Save the Children Mexico.

What we found

Governments widely support the inclusion and protection of all children in education. Globally, almost all responding governments (97%) stated they had some level of protection for students based upon gender and disability. Many also recognise the importance of student participation in comprehensive school safety; for instance, more than three in four (79%) governments reported that children of all ages and abilities are included in annual school hazard drills.

There is still more work to be done, however, particularly in preparedness.

79%

Governments reporting that children of all ages and abilities are included in annual school hazard drills

KEY FINDING 8:

Comprehensive school safety begins and ends with children.

Student Inclusion in Risk Assessments

Only one in five (21%) governments provide robust guidance on child participation in school safety plan development. A similar limitation is seen in student participation in risk assessments, where just one in three (35%) governments had adopted widespread student participation.

Why this matters

Comprehensive school safety is, at its heart, about ensuring children are safe and learning at school. While many governments recognise this, a lack of child participation and inclusion in preparedness planning can limit the effectiveness of school safety policy.

Children are experts in their own lives and are able to identify threats that may not be clear to adults. Children can also point out barriers and issues with plans that may not be immediately clear or known outside of the student body.

When part of the assessment and planning process, children also become equipped with the knowledge they need to adapt and respond. This helps to build a child-centred culture of safety, starting with education but spreading to the whole community.

What should change

All governments should:

- Develop, disseminate, and implement guidance on student participation in risk assessments and safe schools planning at the school and local level.

- Ensure student voice is part of national or sub-national risk assessments and safe school policy and planning.

Conclusion

With every year, the likelihood of crises increases and their impacts deepen. Storms become stronger, heatwaves more intense, conflict more acute, and health risks spread.

But in this picture of increasing challenges to education, hope emerges. The Comprehensive School Safety Policy Survey revealed that governments around the world are taking concrete, comprehensive measures to ensure every child realises their right to learn. While there are clear areas for improvement, as this brief highlights, there is progress to build on. The Comprehensive School Safety Framework can help guide further action, ensuring no child is left behind and no hazard forgotten.

Princia, 9, attends public primary school in the Miandrivazo district, Madagascar. To get to school, Princia has to walk for about 15 minutes. The road is very busy and she is often afraid of being hit by a car or attacked by a zebu. Princia and her classmate Tafita are members of the school’s Disaster Risk Reduction Club.

Copyright: Roni Ahmed / Save the Children.

GADRRRES encourages all countries to:

- Endorse the Comprehensive School Safety Framework, committing to work towards implementing and institutionalising the 3 pillars and foundation of the CSSF.

- Implement the Framework, using it to shape policy, programmes, resources, and ways of working.

- Monitor and report on progress implementing the CSSF, sharing impact, updates, and lessons learned with national and global stakeholders.

- Champion comprehensive school safety in your region and across the globe, helping to drive a global movement.

Twin sisters Karen & Ashly, 10, and their mom Vanessa outside their home in El Salvador, ready to go to school.

Copyright: Save the Children in El Salvador

Global Status of School Safety Map

Click on the map to discover sub-national, national, and regional findings from the Comprehensive School Safety Policy Survey.

Where findings are not available, the country either did not take part or chose not to release their survey responses publicly.

You can also view and download the national and regional profiles for the 2024 Comprehensive School Safety Policy.

The Global Status of School Safety is available to download.

Additional resources

The Comprehensive School Safety Policy Survey 2024 was an initiative led by Save the Children and the Global Alliance for Disaster Risk Reduction and Resilience in the Education Sector (GADRRRES), with generous support from the Prudence Foundation. The analysis was conducted by Risk RED. We wish to thank all the individuals and organisations who contributed to the Policy Survey.

The Global Alliance for Disaster Risk Reduction and Resilience in the Education Sector (GADRRRES) was established in 2013 to provide a comprehensive approach to school safety. It is a multi-stakeholder alliance composed of UN agencies, international non-governmental agencies, humanitarian and development organisations and networks, youth organisations, donors/multilateral funds, and private sector organisations that work together to advocate for and support child rights, resilience, and sustainability in the education sector across the humanitarian, development, peace nexus. GADRRRES has regional networks in Asia, the Pacific, the Americas and the Caribbean and West and Central Africa.

All names have been changed for protection.

@ GADRRRES (2025)